Caracterización fenotípica de la retinitis pigmentaria asociada a sordera

Resumen

Introducción. El síndrome de Usher es una alteración genética caracterizada por la asociación de retinitis pigmentaria y sordera. Sin embargo, hay casos con familias en las cuales, a pesar de presentarse dicha asociación, no se puede diagnosticar un síndrome de Usher ni ninguno otro.

Objetivo. Reevaluar fenotípicamente a 103 familias con diagnóstico previo de posible síndrome de Usher o retinitis pigmentaria asociada con sordera.

Materiales y métodos. Se revisaron las historias clínicas de 103 familias con un posible diagnóstico clínico de síndrome de Usher o retinitis pigmentaria asociada con sordera. Se seleccionaron las familias cuyo diagnóstico clínico no correspondía a un síndrome de Usher típico. Los afectados fueron valorados oftalmológica y audiológicamente. Se analizaron variables demográficas y clínicas.

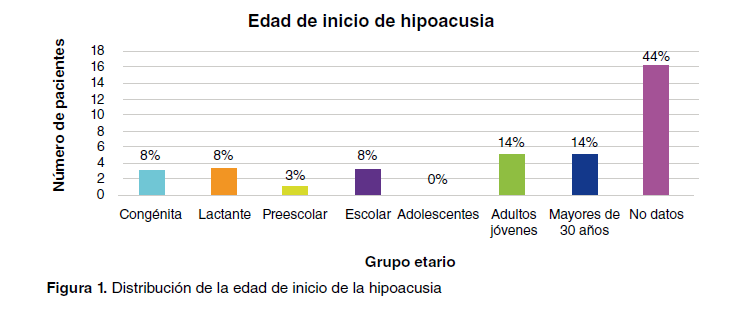

Resultados. Se reevaluaron 14 familias cuyo diagnóstico clínico no correspondía al de síndrome de Usher. De las familias con diagnóstico inicial de síndrome de Usher típico, el 13,6 % recibieron uno posterior de “retinitis pigmentaria asociada con sordera”, de “otro síntoma ocular asociado con hipoacusia”, o en forma aislada en una misma familia, de “retinitis pigmentaria” o “hipoacusia”.

Conclusiones. Es fundamental el estudio familiar en los casos en que la clínica no concuerda con el diagnóstico de síndrome de Usher típico. En los pacientes con retinitis pigmentaria asociada con sordera, el diagnóstico clínico acertado permite enfocar los análisis moleculares y, así, establecer un diagnóstico diferencial. Es necesario elaborar guías de nomenclatura en los casos con estos hallazgos atípicos para orientar a médicos e investigadores en cuanto a su correcto manejo.

Descargas

Referencias bibliográficas

Malm E, Ponjavic V, Möller C, Kimberling WJ, Andréasson S. Phenotypes in defined genotypes including siblings with Usher syndrome. Ophthalmic Genet. 2011;32:65-74.

https://doi.org/10.3109/13816810.2010.536064

Kaplan HJ, Wang W, Dean DC. Restoration of cone photoreceptor function in retinitis pigmentosa. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2017;6:5. 10.1167/tvst.6.5.5 https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.6.5.5

Pakarinen L, Tuppurainen K, Laippala P, Mäntyjärvi M, Puhakka H. The ophthalmological course of Usher syndrome type III. Ophthalmic Lit. 1997;1:36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00130927

Rabin J, Houser B, Talbert C, Patel R. Measurement of dark adaptometry during ISCEV standard flash electroretinography. Doc Ophthalmol. 2017;135:195-208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-017-9614-x

Puffenberger EG, Jinks RN, Sougnez C, Cibulskis K, Willert RA, Achilly NP, et al. Genetic mapping and exome sequencing identify variants associated with five novel diseases. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e28936. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028936

Parmeggiani F, Sorrentino F, Ponzin D, Barbaro V, Ferrari S, Di Lorio E. Retinitis pigmentosa: Genes and disease mechanisms. Curr Genomics. 2011;12:238-49. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920211795860107

Berson EL, Rosner B, Simonoff E. Risk factors for genetic typing and detection in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89:763-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(80)90163-4

Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L. Otolaryngology: Head and neck surgery. 4th edition. St Louis: Wiley Online Library; 2005. p. 2086-99.

Boughman JA, Vernon M, Shaver KA. Usher syndrome: Definition and estimate of prevalence from two high-risk populations. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36:595-603. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(83)90147-9

Cortés RA, Cenjor C, Ayuso C. Síndrome de Usher: aspectos clínicos, diagnósticos y terapéuticos. Tesis. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; 2004.

Tamayo ML, Bernal JE, Tamayo GE, Frías JL, Alvira G, Vergara O, et al. Usher syndrome: Results of a screening program in Colombia. Clin Genet. 2008;40:304-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.1991.tb03100.x

Leal GL, Moyano NG, Tamayo ML. Definición de subtipos del síndrome de Usher en población colombiana. Medicina (Mex). 2010;32:285-94.

Tamayo ML, Bernal JE, Tamayo GE, Frías JL. Study of the etiology of deafness in an institutionalized population in Colombia. Am J Med Genet. 1992;44:405-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.1320440403

Khan KN, El-Asrag ME, Ku CA, Holder GE, McKibbin M, Arno G, et al. Specific alleles of CLN7 / MFSD8, a protein that localizes to photoreceptor synaptic terminals, cause a spectrum of nonsyndromic retinal dystrophy. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2017;58:2906. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-20608

Neuhaus C, Eisenberger T, Decker C, Nagl S, Blank C, Pfister M, et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals the mutational landscape of clinically diagnosed Usher syndrome: Copy number variations, phenocopies, a predominant target for translational read-through, and PEX26 mutated in Heimler syndrome. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2017;5:531-52. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.312

Khateb S, Kowalewski B, Bedoni N, Damme M, Pollack N, Saada A, et al. A homozygous founder missense variant in arylsulfatase G abolishes its enzymatic activity causing atypical Usher syndrome in humans. Genet Med. 2018;20:1004-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.227

Trouillet A, Dubus E, Dégardin J, Estivalet A, Ivkovic I, Godefroy D, et al. Cone degeneration is triggered by the absence of USH1 proteins but prevented by antioxidant treatments. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1968. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20171-0

Orejas J, Rico J. Hipoacusia: identificación e intervención precoces. Pediatría Integral. 2013;17:330-42.

Khateb S, Zelinger L, Mizrahi-Meissonnier L, Ayuso C, Koenekoop RK, Laxer U, et al. A homozygous nonsense CEP250 mutation combined with a heterozygous nonsense C2orf71 mutation is associated with atypical Usher syndrome. J Med Genet. 2014;51:460-9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102287

Namburi P, Ratnapriya R, Khateb S, Lazar CH, Kinarty Y, Obolensky A, et al. Bi-allelic truncating mutations in CEP78, encoding centrosomal protein 78, cause cone-rod degeneration with sensorineural hearing loss. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:777-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.07.010

Ren SM, Wu QH, Chen YB, Jiao ZH, Kong XD. Variation analysis of genes associated with Usher syndrome type 1 in 136 Chinese deafness families. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2021;56:236-41. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn115330-20200407-00273

Lentz J, Keats B. Usher syndrome type II. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. (editors). GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington; 2016. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1341/

Lentz J, Keats BJ. Usher syndrome type I. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. (editors). GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington; 2016. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1265/

Delgado JJ, Grupo PrevInfad/PAPPS infancia y adolescencia. Detección precoz de la hipoacusia infantil. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2011;13:279-97.

Mathur P, Yang J. Usher syndrome: Hearing loss, retinal degeneration and associated abnormalities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:406-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.11.020

Eisenberger T, Slim R, Mansour A, Nauck M, Nürnberg G, Nürnberg P, et al. Targeted nextgeneration sequencing identifies a homozygous nonsense mutation in ABHD12, the gene underlying PHARC, in a family clinically diagnosed with Usher syndrome type 3. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-7-59

Bauer C, Jenkins H. Otologic symptoms and syndromes. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, Niparko JK, Richardson MA, Robbins KT (editors). Cummings Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. p. 2100-15.

Hildebrand MS, Husein M, Smith RJ. Genetic sensorineural hearing loss. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, Niparko JK, Richardson MA, Robbins KT (editors). Cummings Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. p. 1887-1903.

López G, Gélvez NY, Tamayo M. Frecuencia de mutaciones en el gen de la usherina (USH2A) en 26 individuos colombianos con síndrome de Usher, tipo II. Biomédica. 2011;31:82-90. https://doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v31i1.338

Ordóñez J, Tekin M. Deafness and myopia syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. (editors). GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington; 2017. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269029/

Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, Smith RJ. Hereditary hearing loss and deafness overview. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. (editors). GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 2017. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1434/

Nagase Y, Kurata K, Hosono K, Suto K, Hikoya A, Nakanishi H, et al. Visual outcomes in Japanese patients with retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome caused by USH2A mutations. Semin Ophthalmol. 2018;33:560-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/08820538.2017.1340487

Testa F, Melillo P, Bonnet C, Marcelli V, De Benedictis A, Colucci R, et al. Clinical presentation and disease course of Usher syndrome because of mutations in MYO7A or USH2A. Retina. 2017;37:1581-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000001389

Pater JA, Green J, O’Rielly DD, Griffin A, Squires J, Burt T, et al. Novel Usher syndrome pathogenic variants identified in cases with hearing and vision loss. BMC Med Genet. 2019;20:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-019-0777-z

Sun LW, Johnson RD, Langlo CS, Cooper RF, Razeen MM, Russillo MC, et al. Assessing photoreceptor structure in retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2016;57:2428. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-18246

Ayuso C, Millan JM. Retinitis pigmentosa and allied conditions today: A paradigm of translational research. Genome Med. 2010;2:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/gm155

Chassine T, Bocquet B, Daien V, Ávila-Fernández A, Ayuso C, Collin RW, et al. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa with RP1 mutations is associated with myopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:1360-5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306224

Zhang Y, Wildsoet CF. The RPE in myopia development. In: Klettner AK, Dithmar S (editors). Retinal pigment epithelium in health and disease. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28384-1_7

Klettner AK, Dithmar S. Retinal pigment epithelium in health and disease. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28384-1

Park H, Tan CC, Faulkner A, Jabbar SB, Schmid G, Abey J, et al. Retinal degeneration increases susceptibility to myopia in mice. Mol Vis. 2013;19:2068-79.

Gregory-Evans K, Pennesi ME, Weleber RG. Retinitis pigmentosa and allied disorders. In: Ryan SJ, Sadda SR, Schachat AP (editors). Retina. Los Angeles: Saunders; Elsevier; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4557-0737-9.00040-0

Sánchez-Tocino H, Díez-Montero C, Villanueva-Gómez A, Lobo-Valentín R, Montero-Moreno JA. Phenotypic high myopia in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa secondary to a novel mutation in the RPGR gene. Ophthalmic Genet. 2019;40:170-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13816810.2019.1605385

Lu Y, Sun X. Retinitis pigmentosa sine pigmento masqueraded as myopia: A case report (CARE). Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24006. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000024006

Dad S, Rendtorff ND, Tranebjaerg L, Grønskov K, Karstensen HG, Brox V, et al. Usher syndrome in Denmark: Mutation spectrum and some clinical observations. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2016;4:527-39. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.228

García-García G, Aparisi MJ, Jaijo T, Rodrigo R, León AM, Ávila-Fernández A, et al. Mutational screening of the USH2A gene in Spanish USH patients reveals 23 novel pathogenic mutations. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-6-65

Bashir R, Fatima A, Naz S. A frameshift mutation in SANS results in atypical Usher syndrome. Clin Genet. 2010;78:601-3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01500.x

Adam M, Ardinger H, Pagon R, Wallace S, Bean L, Stephens K, et al. Nonsyndromic hearing loss and deafness, DFNA3. In: GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington; 1998. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1536/

Hildebrand M, Thorne N, Bromhead C, Kahrizi K, Webster J, Fattahi Z, et al. Variable hearing impairment in a DFNB2 family with a novel MYO7A missense mutation. Clin Genet. 2010;77:563-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01344.x

Faundes V, Pardo RA, Castillo-Taucher S. Genética de la sordera congénita. Med Clínica. 2012;139:446-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2012.02.014

Antenora A, Rinaldi C, Roca A, Pane C, Lieto M, Saccà F, et al. The multiple faces of spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4:687-95. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.437

Rossi M, Pérez-Lloret S, Doldan L, Cerquetti D, Balej J, Millar-Vernetti P, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: A systematic review of clinical features. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:607-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12350

Giocondo F, Curcio G. Spinocerebellar ataxia: A critical review of cognitive and sociocognitive deficits. Int J Neurosci. 2018;128:182-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207454.2017.1377198

Nolen R, Hufnagel R, Friedman T, Turriff A, Brewer C, Zalewski C, et al. Atypical and ultrarare Usher syndrome: A review. Ophthalmic Genet. 2020;41:401-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13816810.2020.1747090

Algunos artículos similares:

- Patricia Escandón, Popchai Ngamskulrungroj, Wieland Meyer, Elizabeth Castañeda, Determinación in vitro de la pareja sexual en aislamientos del complejo Cryptococcus neoformans , Biomédica: Vol. 27 Núm. 2 (2007)

- Greizy López, Nancy Yaneth Gelvez, Martalucía Tamayo, Frecuencia de mutaciones en el gen de la usherina (USH2A) en 26 individuos colombianos con síndrome de Usher, tipo II , Biomédica: Vol. 31 Núm. 1 (2011)

- Marylin Hidalgo, Claudia Santos, Carolina Duarte, Elizabeth Castañeda, Clara Inés Agudelo, Incremento de la resistencia a eritromicina de Streptococcus pneumoniae, Colombia, 1994-2008 , Biomédica: Vol. 31 Núm. 1 (2011)

- Patricia Escandón, Elizabeth Quintero, Diana Granados, Sandra Huérfano, Alejandro Ruiz, Elizabeth Castañeda, Aislamiento de Cryptococcus gattii serotipo B a partir de detritos de Eucalyptus spp. en Colombia. , Biomédica: Vol. 25 Núm. 3 (2005)

- Fredi Alexander Díaz, Ruth Aralí Martínez, Luis Angel Villar, Criterios clínicos para diagnosticar el dengue en los primeros días de enfermedad. , Biomédica: Vol. 26 Núm. 1 (2006)

- Jorge A. Vega, Simón Villegas-Ospina, Wbeimar Aguilar-Jiménez, María T. Rugeles, Gabriel Bedoya, Wildeman Zapata, Los haplotipos en CCR5-CCR2, CCL3 y CCL5 se asocian con resistencia natural a la infección por el HIV-1 en una cohorte colombiana , Biomédica: Vol. 37 Núm. 2 (2017)

- Jaime Moreno, Olga Sanabria, Sandra Saavedra, Karina Rodríguez, Carolina Duarte, Caracterización fenotípica y genotípica de aislamientos de Neisseria meningitidis, serogrupo B, procedentes de Cartagena, Colombia, 2012-2014 , Biomédica: Vol. 35 Núm. 1 (2015)

- Carmen Lucía Curcio, Andrés Fernando Giraldo, Fernando Gómez, Fenotipo de envejecimiento saludable de personas mayores en Manizales , Biomédica: Vol. 40 Núm. 1 (2020)

- Laura C. Álvarez-Acevedo, María C. Zuleta-González, Óscar M. Gómez-Guzmán, Álvaro L. Rúa-Giraldo, Orville Hernández-Ruiz, Juan G. McEwen-Ochoa, Martha E. Urán-Jiménez, Myrtha Arango-Arteaga, Rosely M. Zancopé-Oliveira, Manoel Marques Evangelista de Oliveira, María del P. Jiménez-Alzate, Caracterización fenotípica y genotípica de aislamientos clínicos colombianos de Sporothrix spp. , Biomédica: Vol. 43 Núm. Sp. 1 (2023): Agosto, Micología médica

- Jenny Andrea Sierra, Leyder Mónica Montaña, Karla Yohanna Rugeles , María Teresa Sandoval , Wilson Sandoval , Karem Johanna Delgado, Jhon Jairo Abella, Salud auditiva y exposición a ruido ambiental en población de 18 a 64 años de Bogotá, Colombia, entre el 2014 y el 2018 , Biomédica: Vol. 44 Núm. 2 (2024)

Datos de los fondos

-

Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (COLCIENCIAS)

Números de la subvención Cod.120372453645. Contrato 656-2015

| Estadísticas de artículo | |

|---|---|

| Vistas de resúmenes | |

| Vistas de PDF | |

| Descargas de PDF | |

| Vistas de HTML | |

| Otras vistas | |